Sitting down to write this while Ramadan is still going on. In fact, this week is a holiday triple-header: Today, Sunday, April 16, is Coptic Easter. Tomorrow is Sham Al-Naseem, the traditional Egyptian spring festival, and Thursday is the first day of Eid al-Fitr, the “feast of the breaking of the fast” which ends Ramadan.

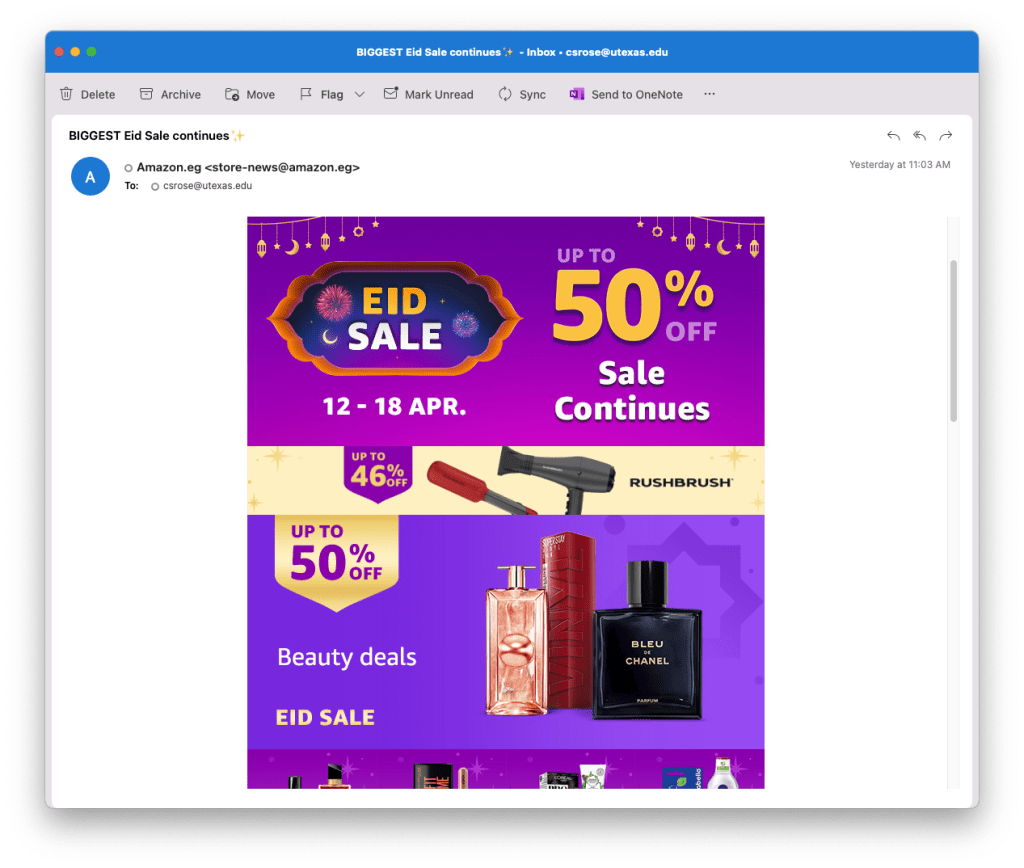

There’s no way to ignore Eid. Look at these ads I got from Amazon:

I’m trying really hard not to read anything into Amazon suggesting that what I need for Eid is a case of deodorant (they also think I need Tide detergent and a jumbo pack of diapers).

So, let’s get into it shall we?

Are there Ramadan decorations like there are Christmas decorations?

Yes…and how!

One of the things you hear over and over in Egypt is that Ramadan is different here than anywhere else in the Islamic world (I have nothing to compare this to, so maybe they say this everywhere else, too).

One of the unique things here is that, as Christmas decorations revolve around various permutations of pine trees (Christmas trees, wreathes, etc.), in Egypt decorating for Ramadan revolves around the fannous, or lantern.

In fact, there are more than a few decorations combining the fannous of Ramadan and the candle associated with the Easter vigil — in Orthodox Christianity the big Easter service is very late on Saturday night; churches descend into total darkness, and then at midnight candles are lit to symbolize the resurrection of Jesus. Traditionally it’s supposed to be a “miraculous flame” but the last time I went to one you could hear them trying to get the lighter to work.

You can find actual lanterns and things that approximate lanterns everywhere, although the best selection is in the area known as Taht al-Rabaa’, in the old city of Cairo between Port Said Street and Bab Zuwayla, and then continuing into the tentmaker’s market, Khan al-Khayamiyya.

How does life change during Ramadan?

I’ll be honest – the first day of Ramadan I really wasn’t sure what to make of things.

So, to answer the question: how does life change? Not much happens between, say, 2 pm and sunset (which right now is around 6 pm — Egypt is doing Daylight Saving Time this year for the first time in seven years, but they decided to push the start back until after Ramadan ends).

The collection I’ve been working in closes at 1:30 and there’s another rush hour as most government offices seem to let non-essential personnel go home around then. Most smaller stores close around 3 so that people can go home to prepare for Iftar (breakfast, which, literally, combines the two words “break” and “fast”).

Then, around 8, things open back up again until 2 am (which is when the government decided things need to close down). Then there’s another meal (suhoor) before fasting starts again for the dawn prayer (fajr), which this morning was at 3:57 am; many people then read the Qur’an (it’s tradition to read/recite the entire text over the course of Ramadan, and during the month Anghami — which is the Middle Eastern version of Spotify — has popular reciters and the section of the scripture for that day ready to go).

So, yes, many people do, in fact, stay up all night and then sleep in the afternoon – I’ve been told this is an Egyptian thing but it seems kind of like it would apply everywhere else, too.

This generally means that by midafternoon, there’s a notable energy lag, which is why not a lot happens after about 2 pm.

The third week of Ramadan is the longest. Even as a non-fasting non-Muslim in Egypt, I have noticed this. The first week people are getting into it, the second week people are in the groove. The third week … is long. The fourth week, everyone’s ready for Eid! Hope you made your plane/train/hotel reservations months ago — everyone travels, and I’m kind of looking forward to having Cairo to myself … or as much as one can in a city of 22 million people.

Ramadan food!

I often tell students (and other groups that I work with) that, while the first comparison that most people make is between Ramadan and Lent, there’s a case to be made that it’s really to Christmas. It’s when people see family, everyone gets together, and there’s. so. much. food. I’ve been to a couple of Iftars and walked out staggering beneath the weight of my own bloat every time. Even when you think you’re done eating, someone will come along and inform you that you’re not.

and so. many. desserts.

Every family has their own traditions. I can’t even start to generalize. Google “Ramadan recipes.”

In Egypt the quintessential Eid dessert is “Kahk al Eid” (or “Eid Cake”). Currently there are signs everywhere for them – and, yes, you can get them from Amazon (although why would you want to??).

It’s alive!

So, a couple of weeks ago I did a photowalk in the Old City at night to see all the Ramadan doings (a photowalk is where a group gets together and wanders around and takes pictures of things). I had been told that if you want to see the “real” Ramadan in Egypt, that’s where to go.

It was noisy. It was crowded. It was on the warm side. And it was incredible.

And just to get a feel for how it was to be there…

There are, of course, many other aspects of Ramadan I didn’t address here, but this has been my experience — so far. If things get wild during Eid, there might even be a part 3!

Also, for the educators out there, my videos are Creative Commons licensed!